Note: In an effort to write extensively about everything I read in a year, I have decided to release in a series of articles my distilled notes and review of a work which is not very well known in the English-speaking world: Jan Patocka’s Heretical Essays in the Philosophy of History. I hope you find them interesting. Let it also be known that it has been years since I have engaged any work of phenomenology, particularly of a Heideggerian orientation, so if you are well acquainted with this point of view you may find my exposition of it lacking, otherwise I hope it proves to be a helpful introduction. There are six essays in the book and an appendix. This is my coverage of the first essay. I have tried to present everything without my own criticism or opinions, although this is doubtless my own interpretation of this book.

The foundational problematic of all modern philosophy resides in how one might relate the general terms “subject” and “object”; a problem which can be indicated in one way by asking what the natural world is, both in itself and for us. The early mechanical philosophers treated the world as a kind of subjective reproduction that faithfully mirrored an external reality. But this view foundered on the problem of the inaccessible “interior” of the observer: if the world is reproduced only upon contact with some causal mechanism outside the subject, then the subject’s inner life becomes an opaque nexus through which all of reality must pass. The first difficulties of this view were then effects of attempts to turn away from the interior world of the observer, that is, to turn away from an explanation of objectivity by an exterior causal effect on the subject. This led to various structural monist interpretations, wherein the genesis and life of both subject and object were understood in terms of relational functions of matter. The explanatory power of this method, both in terms of describing what role our bodies play in engaging with the world and in terms of human "spiritual" self-understanding was limited. This is where phenomenology comes in.

For Husserl, the natural world could not be grasped in the way that science grasps things, but only as a phenomenon, an appearance, meaning that the question is not a matter of what the world is structurally but how it itself presents itself to us in pre-scientific, pre-theoretical apprehension. We must be able to systematically describe how the world presents itself in order to know why it presents itself in this way. Philosophy hitherto had been concerned with the image of the world provided by the natural sciences, where, in its attempt to solve the aforementioned problem of “explaining” objectivity and its relation to the senses, assumed the need to salvage the same paradigm of a subject-object division which produced this problem in the first place.

To account for how the world presents itself is to also recognize the basic comportment of consciousness towards what is presented. It is here, in pre-scientific apprehension, that we find the "originary presence" of the concrete world, wherein consciousness contains within each and every act an intention towards some thing which appears to it. It bears within itself objectival meaning. This means that any supposed elusiveness of objects is itself the result of an essential correlation of acts on the part of this self-same intentional life in relation to that which appears to it. This character of an “immanent transcendence” is explained by the fact that any act of consciousness bears intentionality within it, an objective directionality, so to speak, which supposes some sort of meaning. This “acting” at the depths of naive consciousness is what Husserl calls the pure phenomenon. The term “pure,” while having a certain Kantian transcendental resonance, does not indicate a structural, a priori, unvarying condition of knowledge, as we are again bracketing epistemic questions and the possibility of theoretical cognition. Instead, pure here refers to precisely the mode of appearance intrinsic to this basic, naive, pre-theoretical disposition of the consciousness for whom there appears anything at all.

The pure appearance of intentionality is the appearance of a transcendental consciousness, meaning that intentionality is not simply the way in which a conscious organism relates to the objective, as a property of that organism, but it is the condition for any manifestation whatsoever, including of the organism to itself. The structure of the being for whom there is a world manifested is one in which consciousness precedes any manifestation; but consciousness arises only in its intention towards what is manifest.

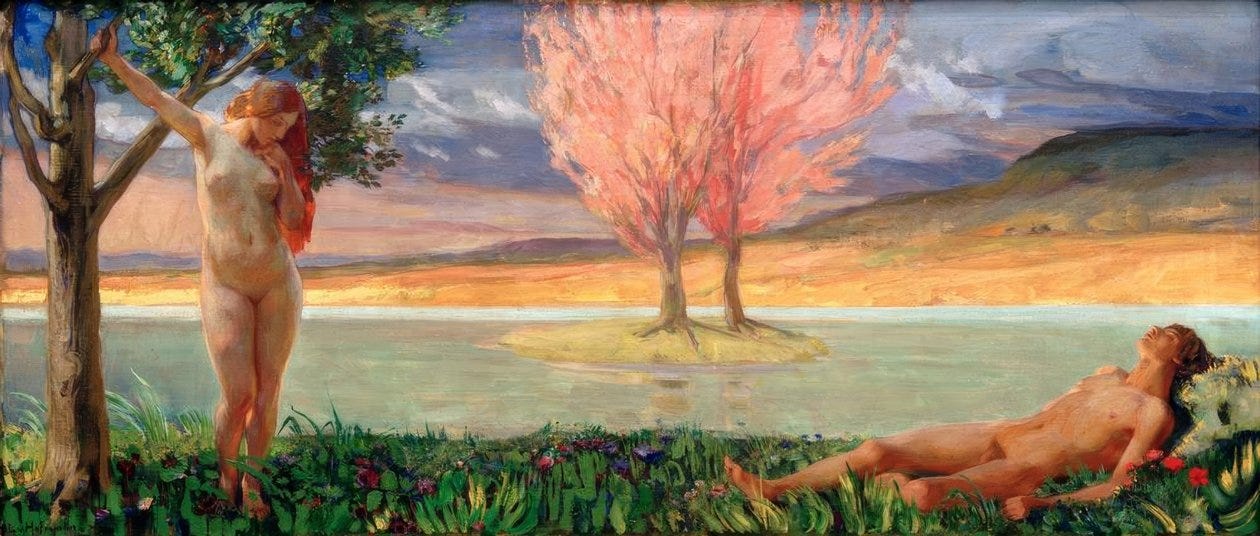

Heidegger reframed this in terms of the unique disposition of the human, which resides within its need to constitutively relate itself, not simply to what-is, but to this very fact of "is-ness," to the fact that there is anything at all; to being as such. The world does not simply appear, but appears as something to be known, in both the rational and erotic-experiential sense of the word. Only the human is open to the world in this way. Its not to say that the human is ontologically privileged, that it can reproduce being within itself, but that its "discovery" of the question of Being is in itself the self-presentation of what there is. The question of being is what makes Being known, however unknown and confusing it remains in such a presentation. From what I can recall, Heidegger formulates the event of such a discovery in terms of the child-like curiosity and wonder at the fact that there is something rather than nothing. For Patocka, and I believe also for Heidegger, "Humans in their inmost being are nothing other than this openness [to Being]."

Openness designates the possibility of being human

…

Humans are neither the locus where what there is arises in order to be able to manifest itself…nor are human “souls” some entities in which phenomena would be reflected as the effects of an “external world.” Humans offer existents the occasion for manifesting themselves as they are because it is only in there being-here that an understanding of what it means to be is present.

In short, the presence of something to a human suggests the possibility of an understanding of the very fact of presence itself, which recognizes it as that thing coming into its own being, phenomenally. There is a basic continuity between Being and phenomena; for anything to be, it must appear—it must become a phenomenon. This obliges us to not take them as “subjective things,” overcoming both the metaphysics of natural science and idealism. As many will know, the word phenomena derives from the Greek phaino meaning to shine forth, to step forth into light. Every appearance is an unconcealment. And by the same token, whatever enters into the horizon of openness does so only against a concealed background, receiving its phenomenal character from something concealed.

The crucial point here really is that openness, in expressing a possibility, suggests varying degrees, where such a possibility may be widened or narrowed. The degree of the potential phenomenalization of what-is is historically dynamic. Intentionality is never purely individual; it is historically and intersubjectively constituted openness.

The region of openness is not identical with the universe of what-is, but is, rather, that which can be uncovered as existent in a particular epoch.

The structure of the way that what-is can appear to humans is subject to change.

Through language, but also through myth, religion, art, ways of life, there are developed and transmitted “modes of openness.” Our ability, or lack thereof, of living historically, that is, of maintaining a cognizance towards inherited modes of openness, will shape the way in which the world appears, not simply to us as individuals, but to humanity, or groups of people as a whole.

Openness is ever an event in the life of individuals, yet through tradition it concerns and relates to all.

In approaching the world phenomenologically,

The things we encounter are grasped as themselves, though not independently of the structure of as what they appear, nor independently of the emergence of essential concealment into openness.

Things cannot but manifest historically. But here we are taking it in the primary sense, that the understanding of what it means for anything at all to be manifest—the way in which the question of being emerges for us—is a necessarily historical encounter, as both the human comportment towards such a question and the corresponding range of potential phenomenalizations are subject to change, and always occur within historical time.

This does not mean that the problem of the natural world has been or even can be solved. At least, it cannot be solved insofar as the problem suggests that “behind” all appearances there remains a primordial, original, and invariant “something.” There can be no invariant precisely if and because what-is is a synthetic manifestation of a world which steps out from a background of concealment and which does so in history, meaning that such worlds “qua syntheses, must be something original.” Even though we are physiologically the same as the ancient Greeks, we do not perceive in the same way—and we therefore do not even perceive the same things.

Historical worlds do perhaps approximate each other at the level of everydayness, but that level is in no sense autonomous.

Yet, just as we do not do justice to the originary “concrete richness” of the world in pre-theoretical consciousness, neither does the “primordial historicity of the world” manifest itself in its fullness. Patocka will, throughout the course of these essays, indicate the significance of the historicity of openness entering into the sphere of openness itself. This process of entrance is a historical unfolding.

Suffice it to say then that the prehistorical is precisely that mode of living for which the mystery of manifestation and concealment is not encountered. Of course, the sacred, the demonic, the mysterious are decisive elements, but mystery as such, as a problem which puts the nature of life itself into question, is not here experienced. The prehistorical is the pre-problematic—there is a dominant degree of self-evidence.

[In the prehistorical situation,] between humans and the world, individual and group, community of humans and the world there are recognized relations which to us seem fantastically arbitrary, contingent, and nonfactual, but which are systematically and strictly respected. It is a highly tangible life which has no other idea of life than living.

The basic disposition here is one of acceptance. The acceptance of life as short and ever defined and confined by the need to toil for the means of living. Life is the struggle to attain the means of life in perpetuity, in a manner which admits of no progressive development and improvement of such means, being as they are sanctioned by the inherited and inviolable rites and cults of the community. Life is bonded to itself. At the same time that labor implies the finitude of life, the problematic character of life, its very activity, in sustaining life, obscures this fact.

Human labor presupposes a relation to time and space which is, in principle, free. The fact that humanity, in contrast to animals, does not have some specific and fixed form of labor allotted to it by nature of instinct makes it capable of an indefinite range of acts and indefinite modes of acting. Labor, which is in the prehistorical setting only labor for consumption, for the immediate continuation of life which bonds life to itself (i.e. life is forever yoked to the mere maintenance of life), is nonetheless possible only on the basis of the freedom which human labor implies.

It was work that for a very long time was most able to keep humans within the context of bare, mere survival.

History is not the history of work, of bare survival, but the history of work reaching beyond itself in a unity with production. Production, although not separate from work, is here distinguished from it as that form of activity which self-consciously and systematically seeks to erect a human world of futural extension, over and above a “natural” existence. The city, its wall and temples, the marketplace, and writing bear the imprint of this development. Life, aware of its bondage to itself, renounces itself and its freedom for the sake of something greater than this. This is why in the first civilizations freedom is defined in terms of the right to not work, and why the divine are associated with not working.

The relation between the aristocracy and the laboring class reflects that of the human community as a whole and its relation with the divine. The gods are not in principle above labor, however they are those for whom labor is not a direct condition of life, but an indirect one—this condition having been conferred upon humans. The works of the gods, as of the aristocracy, are not concerned with daily bread, but order, creation, beauty, and the preservation of the conditions in which such things are possible. Within this context, the labor of humans acquires a meaning beyond the mere preservation of life, being as it is now inextricably linked with the continuation of an historically emergent mode of existence—participation in a divine, supernatural order. The mythic motif of divine retribution in the character of natural catastrophes which jeopardize or wipe out the entirety of civilization speak to the precarious nature of such a balance—there is nothing more evil than being reduced, to regressing back to a state of nature, to a life where all life is in bondage to itself.

This all indicates a changing function of labor as a mediating relation between life and death, or more properly, between the basic nature of life as transient toil and its possibility of attaining something persistent and undying, something beyond itself. In this way, the the primitive, prehistorical practice of filial piety changes in character.

The house ceased to be the core of the world as such, becoming simply a private domain alongside and juxtaposed to which there arose, in Greece and Rome, a different, no less important public sphere. Starting from this thesis, we shall, in what follows, endeavor to demonstrate that the difference is that in the intervening period history in the strict sense had begun.

At it’s highest development, mythology insulates not simply individuals, but entire human communities from the problematic character not only of their own lives, but of the whole fact of manifestation and concealment. In order for a human community to not simply take on the character of a household at the scale of an entire group of people, in order for it to grasp the conditions of its own manifestation, it must move from acceptance to interrogation. It must pose manifestation as such as a problem. Once the possibility of such an orientation is discovered, humans are set out on “a journey from which they might gain something but also decidedly lose a great deal. It is the journey of history.”

History is a risk. A departure from which there will never be any return, lest it ends in annihilation. It tears the entire development of society theretofore from its accepted cyclicality, leaving its potential meaning totally open to question and up in the air, all for the sake of yielding something even greater; a horizon of manifestation hitherto unknown.